When I Googled “National language of China”, I got “standard Chinese”, “Mandarin”, and “Putonghua”. Putonghua is what Chinese in China call the standard spoken dialect of Chinese. Putonghua actually means, “the common language”.

There is no alphabet in written Chinese. There are, however, phonetic “alphabets” which have been created to help people pronounce Chinese correctly. That is one of the reasons why you see so many different spellings for names in Chinese history and literature. The most common phonetic alphabet today is called Pinyin (Lit. “spell sound”).

In Pinyin there are 21 initial sounds and 37 final sounds. An “initial sound is a consonant or a combination of consonants” at the beginning of most syllables. Some syllables don’t start with a consonant sound so those words have no initials. “Finals” are the end sounds of syllables. They are composed of either vowels, combinations of vowels, or vowels ending with a consonant or consonants. In the word “tang”, “t” would be the initial and “ang” would be the final. Most of the sounds are pretty easy to pronounce, but a few need a fair amount of practice to get right.

The hardest part in learning to speak Chinese, however, has got to be the “tones”. Tones are the way you change the pitch of your voice to alter the word you are saying. We do this in English sometimes to show emphasis. If I told Cristy I was planning to bring Xi Jin Ping home for dinner tonight, she would probably say the word “who” in the equivalent of a second tone in Chinese. In English, a “2ndtone” indicates surprise or disbelief. If I asked her if she wanted to eat dog tonight, she would probably answer with an emphatic “no” which is similar to a 4thtone in Chinese; a “4thtone in English” often suggests anger. In Mandarin Chinese, tones are not used like this.

Every Chinese syllable has a tone. Most syllables can be pronounced in a variety of tones, In Chinese, there are lots of homynyms. Many people know that in Mandarin, there are 4 tones. In Cantonese, there is a saying, “9 sounds, 6 tones” ( gau2 seng1 luk6 diu6 九聲六調) which is used to explain sounds in Cantonese. Since I don’t speak Cantonese, however, I’ll fall back on the 4 tones of Mandarin.

Although there are 4 basic tones, there are also half 3rd tones, half 4th tones, and neutral tones. Not to mention tones which change (for a variety of reasons). After teaching Chinese for more than 20 years, I came to believe that the best way to learn tones is not through memorization, but rather through mimicry. It’s great if you can find a native speaker of Mandarin with standard pronunciation who you can attempt to mimic. It’s even better if they will agree to correct your pronunciation and your tones until you get it right.

Using the wrong tone can totally change the meaning of what you are attempting to say. If, for example, I see you after being away from you during the summer and notice that you’ve been working out and are looking healthy and strong, I might say to you, “Wow, you’re looking fit.” You would probably smile and say “thanks.” If on the other hand, I misspoke and instead of saying “fit”, I said “fat”. (“Wow, you’re looking fat.”), you would probably be upset. All I did was miss one vowel. A missed tone on a Chinese word can mean the difference between a “mother” (mā) and “horse” (mǎ).

Try repeating this with a Putonghua speaker:

mā, ma, qí, mǎ (Mom rides a horse)

mǎ, màn (The horse is slow)

mā, ma, mà, mǎ (Mom curses the horse) (mom 媽 Mā) (horse 馬 Mǎ)

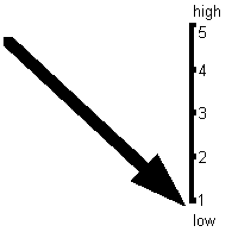

Finding your own range: Try singing and sustaining the syllable “ma” on as low a musical note as you can sing it. We will call that the lowest point on your range and will label that level 1. Now take the same syllable and speak and sustain it this time at your highest comfortable range. We will call the highest point on your voice range level 5. Your normal level of speech would be level 3.

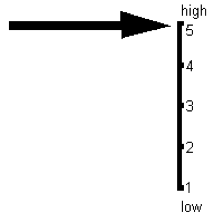

The 1sttone begins at level 5 and ends at level 5. Try saying ma and tang, in first tone.

The 1sttone is indicated by a level line over a vowel (usually first vowel) ( ― )

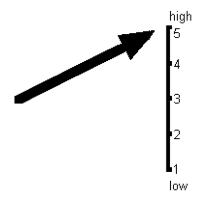

The 2nd tone begins at level 3 and ends at level 5. Say ma and tang in second tone.

The 2nd tone is indicated by an ascending line (bottom left to top right) over a vowel ( / )

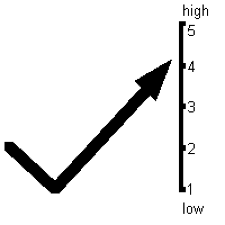

The 3rd tone begins at level 2, goes down to level 1 and ends at level 4. Say ma and tang in the third tone. The 3rd tone is indicated by a v over a vowel (usually first vowel) ( v )

The 4th tone begins at level 5 and ends at level 1. Say ma and tang in fourth tone.

The 4th tone is indicated by a descending line (top left to bottom right) over a vowel ( \ )

I once went into a restaurant in Taiwan in the winter time hoping for a bowl of hot soup. I asked the waitress, “Ni you mei you tang?” (Do you have soup?) She replied, “Women zheli mei you tang. (No we do not have candy here.) I pointed to the menu, and and proudly said “Zhe shi bu shi tang?” (Isn’t this soup?). She laughed and said, “You didn’t say Tāng (soup), you said Táng (candy). We don’t sell candy at our restaurant.”

Chinese Odyssey 11

So where were the rickshaws?

There were taxis and busses.

Clothes looked just like mine

There were no thems or us’s.

I learned 1,2,3,4

now as “yi, er, san, si”

And those things I called “chopsticks”

were really “kuaizi.”