When I was in junior high, my parents sent me to Camp Garland, a Boy Scout camp near Locust Grove, Oklahoma. Flowing through the camp was Spring Creek, a pristine watershed, amazingly clear and refreshingly cold. It reminded me of Montana. There was a small feeder spring flowing into Spring Creek that sometimes I would visit. It flowed down the side of a steep cliff and settled onto a natural rock table. I would sit on the table rock and watch the water flow over and around the rocks and algae, through the myriad of plants growing there. Of course, there were lots of bugs, butterflies, and birds and sometimes I’d glimpse minnows darting in and out of the rocks. The longer I sat, the more I became mesmerized by my surroundings, and mini-me would leave my body and wander down by the water (which had become a roiling river), climb up the clefts in the wall and discover paths that would lead from the pools on the table rock up the cliffs all the way to the mysterious source of the crystal clear water below.

When I first began to really look at Chinese landscapes, I was reminded of Spring Creek. I found myself being drawn towards the mountains, disappearing into clouds, and strolling beside rivers. Sometimes in the paintings there were other people walking there as well. Landscapes weren’t limited to natural landforms and water. There were pagodas and temples and markets.

Perhaps the most famous wandering painting of all is “Along the River during Qing Ming” (清明上河圖 Qīngmíng Shànghé Tú) which was painted more than 800 years ago during the Sung Dynasty. In this amazing glance at what we now know as the city of Kaifeng in the province of Henan (then China’s capital), we find ourselves walking through the painting with our eyes. In our walk, we get to experience Sung Dynasty daily life as we stroll past merchants, laborers, sedan chairs carrying scholars, restaurants and taverns, people loading and unloading boats along the Bian River (汴河 Biàn Hé), donkeys bringing in firewood from the outlying areas. And the action isn’t limited to the paths, roads, and bridges. Much of what happens in the painting is on the river itself. Only 10” (25 cm) in width, it stretches over 17 feet (about 5 meters) in length. Starting at the far right, one inches left across the painting savoring the journey; stopping sometimes to shop in the market or grab something to eat on the Rainbow bridge.

“Qingming” is a day to remember one’s ancestors. Some people call it “grave sweeping day”. Families will visit cemetaries on this day. They will tell stories, picnic, and tidy up the plot by sweeping the grounds, repainting the writing on the tombstones with red paint and they will burn incense. Qingming is not a sad day, but a day of thanksgiving and rememberance.

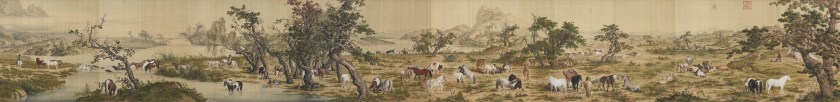

Some Chinese paintings feature a hundred things like children or birds or butterflies. Giuseppe Castiglione (郎世寧, Láng Shì Níng), the Italian Jesuit brother and imperial painter for three Qing Dynasty emperors during the early 18th century, has a famous painting in the Palace Museum in Taipei of 100 horses. Even though he painted in classic Qing style, there are elements in his art that definitely speak to his western origins.

Chinese Odyssey 16

The bowl was her family’s

since she was a child.

The painting inside it

so natural and wild.

There were mountains surrounding

a natural pool

where young kids were playing

decidedly cool.