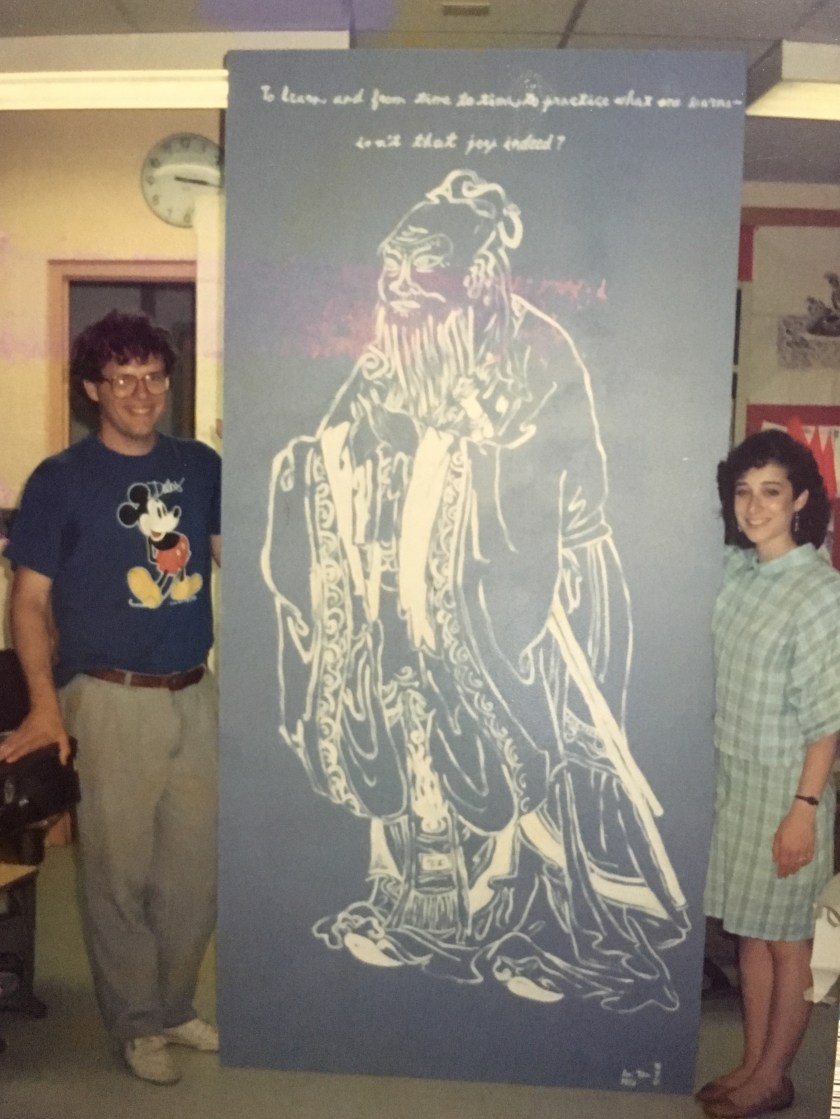

The Master said: “To learn, and from time to time, to practice what you learn, isn’t that joy indeed?”

The Master said: “To learn, and from time to time, to practice what you learn, isn’t that joy indeed?”

My first introduction to Confucius was in primary school, where we would share “Confucius says” pearls of wisdom that, I’m pretty sure, Confucius never said. Still, even as nine-year-olds, we all knew the name, Confucius. I can’t think of any other Chinese historical figure that has that kind of name recognition.

The writings and teachings of Confucius are one of the “3 pillars of Chinese Culture”. The impact of Confucius on, not only China, but on Japan, Korea, and much of south-east Asia, is immense. In much the same way as teachings from the Bible, the Quran, and the Torah continue to influence the way people behave today, Confucianism continues to inform both behavior and relationships in China. Yet, Confucius was not a religious teacher.

The man we call Confucius is known by most Chinese as Kongzi (孔子 Kǒngzi), or Kong Fu Zi (孔夫子 Kǒng fū zǐ.) Born in B.C.E, 551, Confucius lived in the “Spring and Autumn Period” during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (東周 Dōngzhōu), about 500 years before the birth of Christ. He was born in the town of Qufu (曲阜 Qǔ fù) in the province of Shandong.

Confucius believed that the sages of old truly understood social harmony and had, through the Book of History (書經 Shū Jīng) and the Book of Odes, (詩經 Shī Jīng), made that wisdom available to people living during the time of Confucius. By studying both Zhou and Shang societies, religion, and political institutions, the chaotic state of affairs which existed during the Spring and Autumn period could be rectified. In addition to the classics, there was also a rich oral history that surrounded Confucius. He loved hearing stories of the legendary Kings preceding the Zhou Dynasty. He recounted many of these stories and lessons of life in the Analects (論語 Lúnyǔ), a collection of his thoughts and dialogues with his disciples. The Confucian Analects is one of the Four Books and the Five Classics (四書五經 Sìshū Wǔjīng), which are the classical texts compiled after Confucius’ death, and which make up the core of Confucianism.

Confucius felt it was his mission to instruct rulers at high levels of government in order to revitalize learnings that had been around for centuries. He believed that the rites, rituals, and ceremonies (礼 lǐ) had been developed over generations of human wisdom and that they both represented core social values and helped create social order. Confucius also stressed virtues like ren (仁 rén), sometimes translated as “righteousness” or “humanity” or even “love” or “kindness.” How do human beings live together in harmony? Only by continuing to nurture our own inner character through education and reflection.

One of the ways that people could begin to live in harmony was to adhere to the three fundamental bonds ( 三纲 Sān Gāng), which are the basis for the most important of human relationships. Although one cannot discount a hierarchy, there is equally a sense of reciprocity and definition of roles in these relationships. The ruler not only mentors the ministers but takes care of them (君臣 jūn chén); the father teaches, encourages, and protects the son (父 子 fù zǐ); the husband respects, supports and nurtures the wife (夫 婦 fū fù). They all have obligations to one another.

Confucius was the ultimate idealist. He believed that people could improve themselves and their interactions among their families and their states through love, respect, understanding, and consideration of the needs of others. But core to those requirements was honesty. And that meant being able to criticize unjust rulers and refusing to serve corrupt officials.

The Master said: Water that floats a boat can also capsize it. 子曰:“水可載舟,亦能覆舟”

Good government demanded stellar officials who had mastered the five virtues:

- Li (礼 lǐ), propriety, ritual etiquette, manners, duty, and respect. Confucius clearly identified roles between rulers and ministers, fathers and sons, husbands and wives, elder brothers and younger brothers and even friends.

- Ren (仁 rén), benevolence, or kindness to one’s fellow man. Confucius believed that there should be no limit to benevolence, even if it means laying down one’s life for another.

- Xin (信 xìn), honesty, truthfulness, faithfulness, and sincerity. One’s word is one’s bond.

- Yi (义 yì), righteousness, honesty, integrity; strongly associated with justice

- Zhi (智 zhì), wisdom, knowledge of right and wrong; a strong moral compass

The Master said: One cannot be an outstanding teacher, without continuing to acquire new knowledge.

子曰:“溫故而知新,可以爲師矣。Zǐ yuē: Wēn gù ér zhī xīn, kě yǐ wéi shī yǐ.”

Chinese Odyssey 40

We continued our journey,

in a hard sleeper car,

to the land of Confucius,

a bright rising star.

Now children can learn

about filial piety,

Will little emperors dance

to odes of propriety?