In today’s world, it’s difficult to imagine Catholic Jesuit priests introducing scientific principles and laws into China that would merge with China’s mathematics and engineering to transform Chinese understanding of astronomy. But hang on to your hats. These guys did just that! At the beginning of the 17th century, Matteo Ricci and other priests who followed in his footsteps were convinced that science would open wide the doors to Christianity in China.

The Board of Astronomy became an official part of the Chinese government during the Han Dynasty (right around the time of Christ). Even before that, there are records of Chinese noting celestial phenomena like solar and lunar eclipses and comets. But by the end of the Ming Dynasty, the study of astronomy was definitely on the decline in China. Enter the Jesuits.

Matteo Ricci was not only a priest, but he was also a professor of mathematics whose own professor had been held in high esteem by Galileo. In 1601, upon arriving in Beijing, Ricci was granted an audience with the Emperor Wan Li and he offered his services to the Emperor. During a trip to Nanjing, he had discovered several large antique bronze astronomical instruments which nobody really understood, that had been created by the Chinese astronomer, mathematician, inventor, and engineer, Guo Shoujing (郭守敬) during the reign of Kublai Kahn in the Yuan Dynasty (13th century).

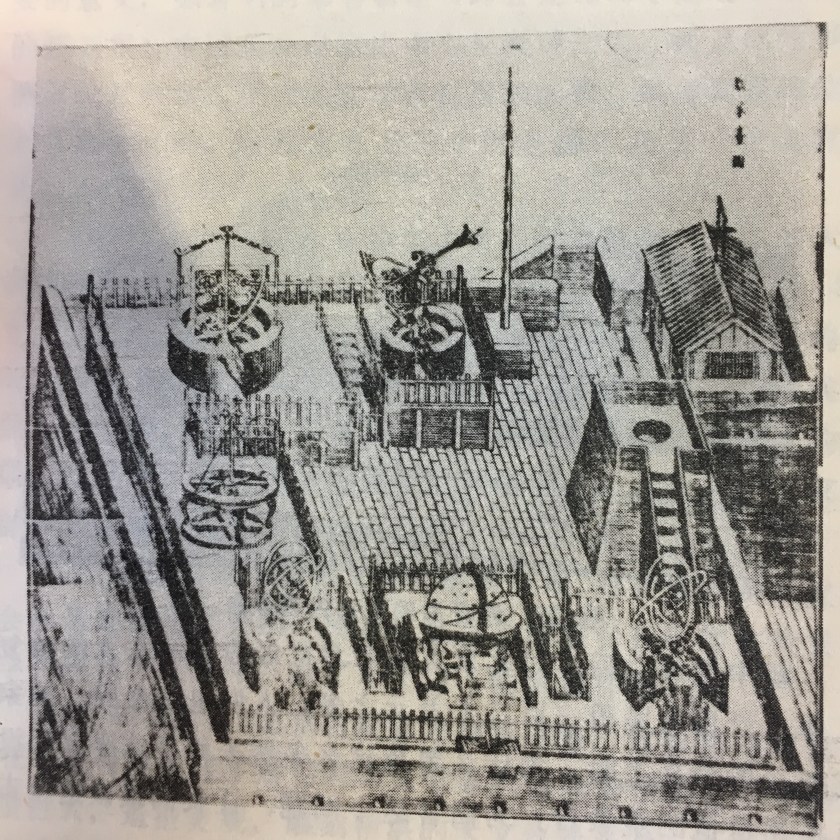

The very cool thing is that these instruments still can be found on the top of a small square building in Dongcheng Qu on Jian Wai Da Jie in Beijing. It’s called the Beijing Ancient Observatory (北京古观象台 Běijīng Gǔ Guānxiàngtái.) The photo above is from an observatory pamphlet I picked up there in the ’90s. I still don’t understand how any of these instruments work.

Not far from the observatory, there are hundreds of hutongs (胡同 hútòng). Hutongs are narrow alleys that have flowed through neighborhoods in Beijing since the Yuan Dynasty (13th century). Like so much of China, what was once a normal way of life has turned into quaint neighborhoods where tourists can rent airbnbs. All the homes and shops are low-rise in the hutong neighborhoods. The houses have courtyards where families sit on stools and lounge chairs made out of bamboo slats. Birds sleep in wooden cages covered to keep them dark and crickets chirp in tiny bamboo cages being fed and trained for cricket fighting. Most people who live in hutong’s live where their parents lived and their parents before them. It’s said that the term, Hutong, actually comes from a Mongolian word meaning “water well”.

Not far from the hutongs is the Forbidden City, across the street from Tiananmen Square, and only a few blocks from Beijing’s first ever McDonalds. Through a contact in Hong Kong, a former student of mine from Australia managed to get an “internship” slinging burgers and running a cash register at what was once touted as the biggest McDonalds in the world. It could seat over 700 people. I wish I could have witnessed this tall white kid joking with his customers there. By the end of the summer, his Putonghua was better than mine. In 1996, this piece of Wangfujing real estate was determined to be too valuable for McD’s and is now the home of the Oriental Plaza.

Chinese Odyssey 46

We ate food from McDonald’s

near Tian An Men Square,

bicycled through hutongs

climbed Drum Tower stairs.

Saw celestial globes

made by Jesuit priests

for the Emperor Kangxi’s

astronomical feasts.