Chinese Odyssey 66

In the Banpo museum

at the edge of Xi’An

There was “Hopi” clayware

and ancient floor plans

In 4000 BC

were the same stories told

in Pueblo kivas and

Shaanxi bungalows?

Growing up in Montana and Oklahoma, both states with large indigenous populations, I learned from my history classes that Indians walked across a land bridge from Asia over to Alaska across the Bering Strait during the last ice age and that the first documented site of an Indian settlement was in Clovis, New Mexico around 13,000 years ago. Lots of pieces were missing, but still, that worked for me . . . at least until I was exposed for the first time to American Indian creation stories in Roger Dunsmore’s Humanities class at the University of Montana. It was also during university, that I finally realized that the study of history was not necessarily static and that new discoveries meant different hypotheses which included the peopling of the America’s. National Geographic articles showing the Olmec stone heads discovered near La Venta, Mexico left me without a shadow of a doubt that not all pre-Colombian Americans were of Asian heritage. In the early 80’s, I took a group of public high school students from Oklahoma to Shanghai for a six week study course. One of the members of our group was a Native American who was constantly being addressed in Mandarin. Mainland Chinese were not only convinced she was Chinese, some insisted that she was Cantonese. She was, in fact, Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee.

There have been many connections made between North America and Asia. I don’t have any doubts that there were people who crossed the Beringia Land Bridge and filtered down through the Americas over the course of thousands of years. I also have little doubt that America was peopled from other parts of the world as well. Some tribes and nations have stories and songs that suggest that they have always been in a particular region of America and I have no proof that they were not.

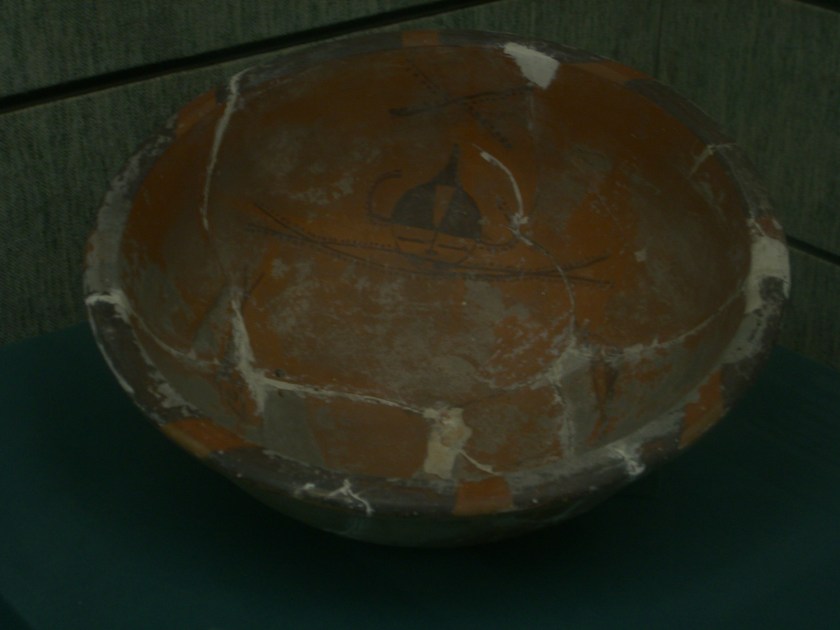

But it was the bowl above that really caught my eye when I walked into the small building that housed the Xi’An Banpo Museum (西安半坡博物馆) in 1982. The clay and the designs were similar to bowls I had seen at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma growing up. But these bowls were Neolithic Chinese, from about 4,000 BCE and they represented what is called Yangshao Culture (仰韶文化 Yǎngsháo wénhuà). Besides Yangshao culture having a presence in the loess plateaus along the Yellow River near Xi’an, remnants and artefacts from Yangshao Culture reach beyond Shaanxi into Henan and Shanxi (note: There is a Shaanxi and a Shanxi). Relatively little is known about the Yangshao people who lived at Banpo other than they were farmers who grew millet, wheat, and sorghum. They understood water and built terraces to prevent flooding. They also built pens for domesticated sheep, pigs, dogs, cattle, and goats.

Banpo was a community of small houses, each 10-16 feet across partially sunk into the ground. This was done to keep the homes cooler in the summer. The houses appeared to be of a wattle and daub variety similar to those of American Indians who lived in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Kentucky. Wattle and daub used wooden strips and/or branches woven into a lattice design and coated generously (daubed) with a mixture of mud, clay, animal poop, and straw. The roofs were conical and made of grass bundled together (thatch) which allowed the rain to run off.

It was the frog, pig, and bird faces, the deer and fish figures, and the geometric designs that really hooked me though. They were made with strong black lines, circles, rings, triangles. Some were etched while others appeared to be pressings of fabric or rope. On some of the pots were cuttings and lines that could have been an elementary form of writing or merely identification symbols. Among the nearly 10,000 artefacts and stone tools that have been uncovered were sickles and plows, bone and stone beads, ceramic bowls, basins, water jars, and urns (both for cooking and for burial). There were also fishhooks, bone needles, arrowheads, stone axes, and knives found in Banpo.

The fact that a cemetery was found very near the village suggested that there were defined burial rites and religion. Near the ancestral bones were found some of the best preserved artefacts of the Banpo people indicating the belief in an afterlife. Of the 130 adults buried there, all were buried face-up with their heads pointed towards the setting sun. Infants and young children were buried differently. They were placed in clay urns with a hole on the top.

In my search for other American Indian/Chinese Connections, I found very little. I did, however, discover two stories that were amazingly similar.

“Smearing the Bell”, was a story that first appeared in Song Dynasty China (960-1279 CE.) After a robbery, a group of thieves was assembled and confronted with a temple bell that had a magical power. If a real thief touched the bell, it would ring. If an innocent person touched the bell, it would remain silent. So the Magistrate placed the bell behind a curtain after ordering his constables to paint the bell. The thieves were then instructed to reach behind the curtain and strike the bell. Each of the men reached in and “touched” the bell, but the bell did not chime. Then, the Magistrate noticed that one of the men who claimed to have struck the bell had clean hands. When the Magistrate confronted the thief, the thief confessed.

‘Children of the Frost’, a story by American, Jack London, author of “The Call of the Wild” (1903), told of an Indian woman in the Klondike who reported to a local ‘Shaman that she had lost a blanket. The Shaman took a raven and placed the raven in a black soot covered pot in a dark room. He then commanded every villager to put their hand into the pot and touch the raven. If a thief touched the raven, the raven would cry out. All the villagers went in, but the raven never cried out. Then the shaman noticed one man with clean hands and confronted the thief, whereupon, the thief confessed. The blanket was found in the thief’s house and was returned to the woman.1”

1Ting, Nai-tung. “A Comparative Study of Three Chinese and North-American Indian Folktale Types.” Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 44, no. 1, 1985, pp. 39–50. JSTOR.

I found two studies of American Indians and Chinese in America during the 19th century which I also found interesting just in case anyone might be interested:

“They Looked Askance”: American Indians and Chinese in the Nineteenth Century U.S. West by Jordan Hua, Honors Thesis, Professor Townsend, April 20, 2012

Horizontal Inter-Ethnic Relations: Chinese and American Indians in the Nineteenth Century American West Author(s): Daniel Liestman Source: Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Autumn, 1999), pp. 327-349 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/971376 Accessed: 22-02-2020 01:03 UTC