Chinese Odyssey 78

The province of Guizhou

was poor and remote.

It’s said there were three things

they all lived without;

no three feet of flatland,

three days without rain,

three pieces of silver

were in their domain.

Xi Jinping, China’s Premier, has been getting a lot of bad press these days, especially in the USA. Most recently due to the Hong Kong national security legislation, but that runs neck-to-neck with the coronavirus. Before that it was unfair trade practices, cyberespionage, the treatment Uyghurs in Xinjiang, and a host of other issues. What we don’t hear about very often, however, are some of Xi’s positive initiatives.

In October 2015, Xi vowed to eradicate poverty among the remaining 70 million poor Chinese people by the year 2020. Actually, the poverty eradication initiative started in 1984 when Deng Xiaoping said in a meeting with foreign guests: “Socialism must eradicate poverty, and poverty is not socialism.” Since the year 2000, 600 million poor people had already been lifted out of poverty. Xi relied on his own experience growing up in a small impoverished agricultural community in the north-western part of Shaanxi province in the 1950’s and 60’s. This year, Xi has reiterated his solemn pledge during the March 2020 18th National Congress of the CCP, that despite Covid-19, this goal shall be met.

Even though, the name Guizhou, could be translated as “rich land”, for most of its history, Guizhou has been one of the poorer provinces of China largely due to topography and isolation. Guizhou sits on an old eroding plateau called the Yunnan Guizhou (aka Yun Gui) Plateau. It’s steep slopes, poor drainage, and red and yellow soil make it challenging for farming. Only about 3% of Guizhou’s land is suitable for any type other than terrace farming and terrace farming requires large numbers of people working for little pay. Imagine not a hill, not a mountain, but a range of mountains sculpted by hand into steps of various sizes and shapes that all need to be maintained by an intricate system of irrigation controlled by massive numbers of men, women, and children using the most basic of farming tools.

Topography also made trade difficult since there were very few roads and no navigable rivers in Guizhou. Guizhou’s does have natural wealth, however, in terms of forests and plant and animal diversity, it is a treasure land to practitioners of Chinese medicine.

To address Guizhou’s poverty, there have been major initiatives throughout the province. New crops have been introduced that are more nutritious and have higher yields, both in terms of production and health benefits. Over 4,000 miles of new roads, highways, and modern suspension bridges have been built reaching some of the more isolated areas in the province. A well known idiom in China is 要想富先修路 yāo xiǎng fù xiān xiū lù which translates to, “If you want to become prosperous, you must first build roads.” In 1978, there were 18 million people living in poverty in Guizhou. 40 years later, in 2018, that number had been reduced to 1.5 million.

In December of 1934, after trudging 320 miles from Ruijin, Jiangxi, the 34th Division of the Red Army was nearly destroyed by Nationalist Troops at the Battle of the Xiang River (血战湘江) in Guangxi province. By the end of that battle only about 30,000 of the original 130,000 Red Army troops remained and things were looking bleak. With their strong reduction in numbers, they knew they would have to jettison much of their equipment, like x-ray machines, printing presses, and heavy artillery, so they dumped it into the Xiang River and carried on. Mao persuaded Zhu De, Lin Biao, Zhang Wentian aka Lo Fu, and others that they should change course and meet up in Zunyi in Guizhou instead of south-eastern Sichuan. By the time they reached Zunyi in Guizhou in early January, 1935, it was clear that tactics and leadership needed to change. Otto Braun, the German comintern commander of the 1st army alongside Zhou En Lai and Bo Gu aka Qin Bangxian were poised to step aside. By the end of the Zunyi Conference (遵義會議 Zūnyì huìyìn) January 15-17, 1935, it is fair to say that Mao Zedong was poised to take over as both military commander and acknowledged leader of the Chinese Communist Party. It’s probably no coincidence that China’s premiere “baijiu” (grain alcohol), Maotai (made from red sorghum), is distilled only minutes away from Zunyi.

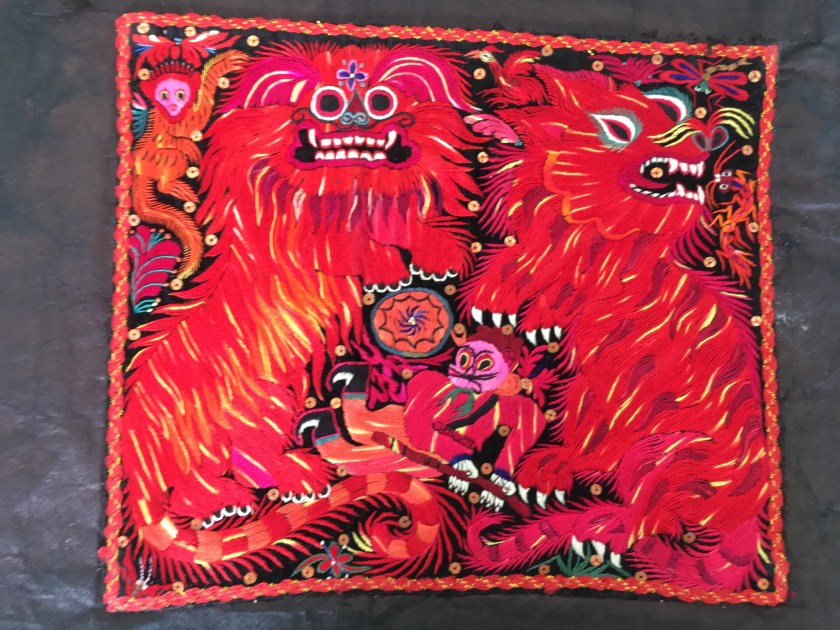

According to legend, the people from the Miao minority in Guizhou came from one of a dozen eggs laid by a butterfly mother who came from a Maple tree. Among the remaining eleven eggs there was hatched a dragon, an ox, an elephant, a tiger, a thunder god, a centipede, a snake, a boy and a girl. Miao religion is animistic in nature. Shamans communicate with spirits. Animals, stones, trees, water, lightening, and thunder all play important parts in traditional Miao religion. The embroidery of the Miao people is striking. The photo is of a portion of a sleeve which we discovered in a house outside of Kaili in western Guizhou. The two lions depicted represent the autumn harvest celebration and the deep red color symbolizes fortune and prosperity. The cotton fabric was made by the Miao people and dyed red to become “cow blood fabric.” The fabric is often coated with egg white to give it a kind of sheen or gloss and to make the fabric water resistant. Indigo is also prevalent in Guizhou. Blue indigo actually comes from green leaves. Indigo leaves are crushed and left in a vat of water to ferment. After a few months, quick lime is added and the result is indigo. Cotton fabric is soaked in the dye and then hung to dry. If the color is not dark enough, the fabric may be dipped again until it reaches the desired shade of blue. Indigo is still the primary dye used in making blue jeans. Sometimes hemp is used instead of cotton and similar techniques are used to preserve the hemp cloth. Hemp fibers, however, are much shorter than cotton and unsuitable for spinning.

Besides the beautiful embroidery, Miao people are also silver artisans. Miao women adorn themselves with an abundance of silver jewellery which typically includes necklaces, earrings, bracelets, rings, and even heavy silver tiaras and crowns. Sometimes these crowns are adorned with silver horns or head flowers. Women wear silver “vests” decorated with all kinds of bling. Silver is also used by the Miao to test the purity of water and to fight disease and misfortune. Like many arts in China, however, silver artisans are a dying breed. Like embroidery, this art is time consuming and takes patience and persistence. But the results are both delicate and elegant.

If you were to meander through Zhaoxing, the largest and most accessible Dong village, in far eastern Guizhou, you couldn’t help but feel that you’ve entered a time warp. The village rests in an idyllic setting surrounded by jade colored hills with a river flowing through it. The houses are almost all constructed of wood with many built on stilts. There are five drum towers, one for each of five Confucian virtues: Ren 仁 (benevolence), Yi 义(righteousness), Li 礼 (ceremony), Zhi 智(wisdom), and Xin 信 (integrity). Each is unique, both in style and design.

Imagine a covered bridge made of wood that was wide enough for a bus to go over, but was made for people, not vehicles. Held aloft by five rectangular pillars made of concrete and stone, it’s an open bridge which supports multi-level towers (one on top of each pillar). There are benches and railings along the entire distance of the bridge where old men are playing xiangqi (Chinese chess), young couples are courting, and people of all ages are playing and exercising. All along the bridge and on the walls of the towers are carved and painted works of art. Calligraphy and auspicious flowers, dragons, gourds, cranes are everywhere. And lest I forget, strong mortise and tenon joints alleviate the need for a single nail or screw. These are the Wind and Rain Bridges of the Dong minority.