Chinese Odyssey 83

The map that I’d found

when I was pre-teen

Each mountain and river

were places I’d seen

The words without letters

I now understood,

See, the writing was mine

And it looked pretty good.

Someone once told me that China looked like a big chicken and someone else showed me how Taiwan look like a sweet potato. To one who has always struggled with creating visual art, that worked for me. Although I have a vivid imagination, I’ve always found it virtually impossible for me to transfer my ideas into visual images. I have, however, always loved looking at drawings, paintings, sculptures, photos – all kinds of art. I marvel at not only the art work I contemplate in museums, but equally at that produced by my students and my daughters over the years and imagine the map in my poem looking like something Chinese artist Wang Yani might have drawn.

One of the most extraordinary artists and presenters I’ve had the fortune of seeing , fourteen year old Wang Yani stood very still on a dais in a small lecture hall at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri in 1989. A large sheet of white paper was placed on the ground in front of her on the stage and for a few moments, Yani just stared at the paper. Then something happened. She reached down, picked up a brush, mixed some colors on a palette and began to lay blotches of black, brown and red onto the paper. Once she started, she could not be stopped. Each stroke was intentional and meaningful. Yani moved swiftly from one area of the painting to another with an intensity that entranced her audience. Truth be told, I can’t remember if Yani painted monkeys or cats or cranes that day, but I do remember that in the span of 20-odd minutes I was looking at a scene that would make any child smile. There were multiple animals playing on the page with trees and jungles and it all seemed to be moving. Yani’s animated art felt alive.

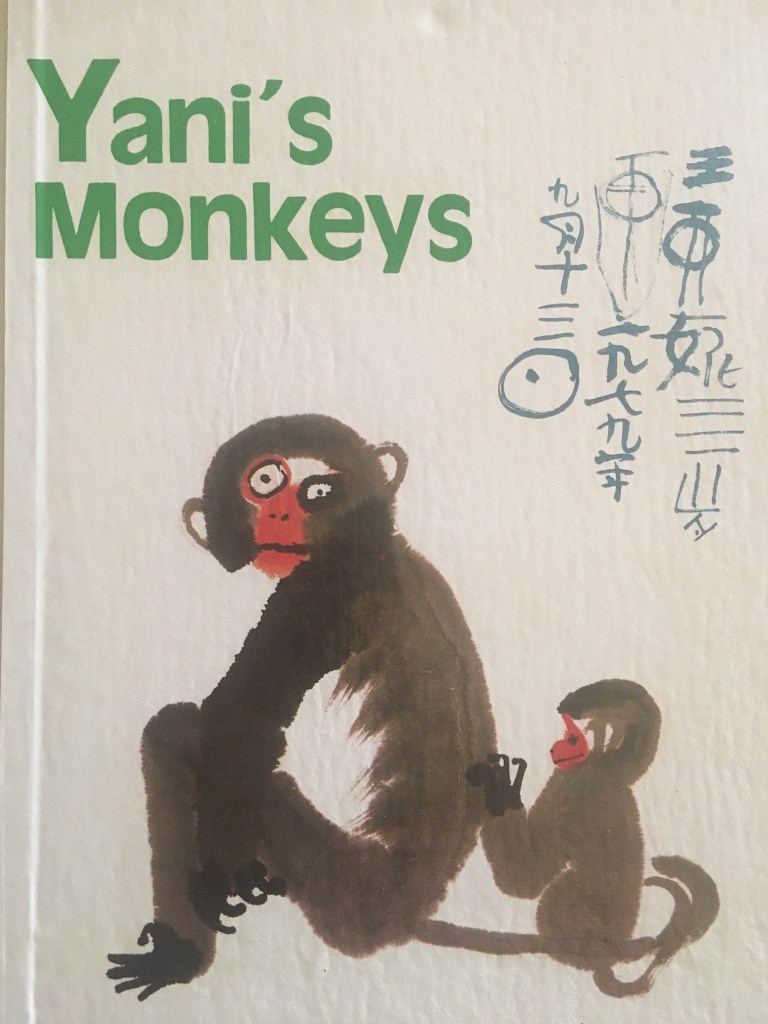

Wang Yani was certainly a child prodigy. First discovered before she was even three years old, Yani painted the picture on the cover of her book at age 4. Wang Yani hails from the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in southern China. In the area where she lived there were tall pine trees, groves of bamboo, coconut trees, and orchards filled with fruits of many shapes and colors. Yani would walk among the trees with her artist father and describe sunsets in clouds and flames that “helped the sun cook its meals”. Yani would gather sticks and twigs and leaves and bark and pretend that they were animals. After a visit to the zoo at age three, Yani developed a fascination for monkeys, the ways that they played and screeched and cuddled.

Yani, for her part, didn’t really understand the fuss. “It’s simple,” she said. “I just paint what I see.” But I continued to be astounded at how that transfer took place. To Yani, every picture told a story. I was reminded of the artist/calligrapher Wang Fang Yu and his painting where he created a painting of Wang Wei’s saying, “In every picture there is a poem and in every poem there is a picture.” Yani’s art has be described as 写意 (xiĕ yì) “Idea writing” aka free lance or literati painting. Images and words appear to be spontaneous and simple but are, at the same time, incredibly detailed, accurate and bold.

Wang Yani’s artist father, Wang Shiqiang, painted in a more traditional, western style. Although he coached Yani on “concentration”, Wang Shiqiang really tried hard not to influence his daughter’s style. In her early years, there were no art books in her home. When Yani’s talent began to really emerge, Wang Shiqiang put his own art tools away, so as not to influence Yani’s work.

I like to imagine that the map in the beginning of the poem was a map drawn in the style of Wang Yani. As a nine-year old boy, my imagination would have included mountains and rivers, bamboo and pandas, and the Great Wall of China. Even though I couldn’t paint like Wang Yani, I inhabited some of the worlds she created. I ran through the jungle bare footed, scurrying up tree trunks, jumping from one tree to another, always finding a branch to grab and a vine to carry me forward. Unlike Mowgli, I was not a “man child.” I’m not sure what I was, since I never focused on me. But like Mowgli, all of the animals, the monkeys, the lions, the elephants, the venomous snakes, and the giant crocodiles were my friends. The trees were my roads, and the pools and waterfalls were my resting places. All my body needed were the fruits and nuts which grew in abundance.

As an adult I see so many more parts of China – its deserts and plains, the Three Gorges river project, its modern cities, Maglev trains, and suspension bridges, and, of course its masses of people. I can’t help but wonder what Wang Yani’s paintings might look like if she had been born in Shanghai or in Hong Kong.