颐园新居[CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, from Wikimedia Commons

颐园新居[CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, from Wikimedia Commons

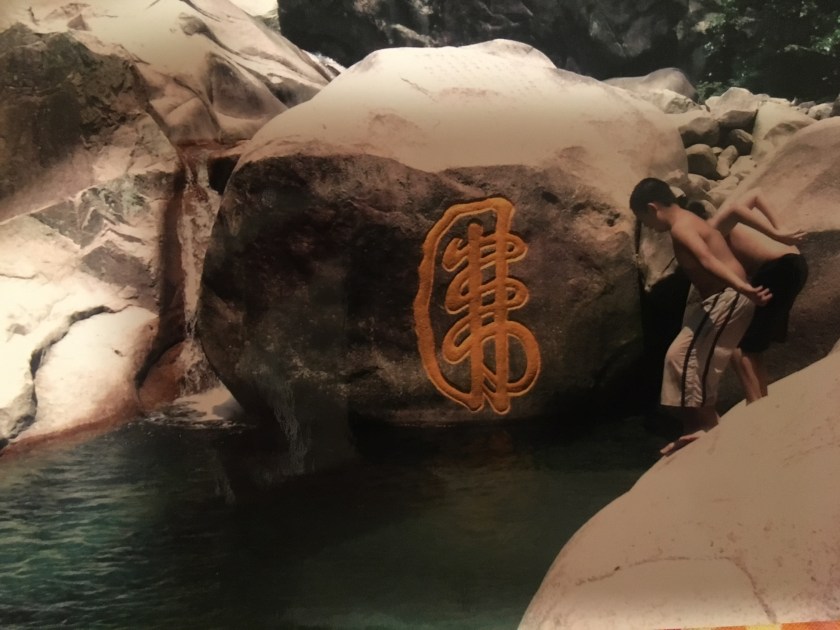

Huangshan is a range of mountains located in the southern part of Anhui province. Photos like this one illustrate the types of natural features that greet those who find their way here. Sunrises, sunsets, peaks, crags, promontories into seas of clouds, pine trees and natural springs abound. Huang Shan is latticed with trails and steps. On these paths, one finds hikers, and artists, painters, and poets. After one visits Huang Shan, the landscapes on the scrolls that formerly appeared magical, finally make sense. They’re real.

More than a thousand years ago, there was a poet and a painter by the name of Wang Wei (王維 Wáng Wéi). Although Wang Wei is acclaimed as one of the great painters of the Tang Dynasty, none of his original paintings have survived. His poetry, however, continues to live.

In 1980, Fred Fang-Yu Wang (王方宇 Wáng Fāngyǔ), a professor of Chinese at both Yale and Seton Hall Universities, published a a book of his own calligraphy called “Walking to Where the River Ends”, where he connected his calligraphy to the poetry of Wang Wei. Although nowhere in this volume is Huangshan mentioned, I can’t help but connect Wang Fangyu’s calligraphy and Wang Wei’s poetry to this amazing range of mountains. Wang Fang-Yu starts off the book with a poem by Su Shih (蘇軾 Sū Shì), an eleventh century poet who wrote of Wang Wei, “in every poem, there is a painting. In every painting, there is a poem.” (Wang, Fred Fang-Yu. Walking to Where the River Ends. Compiled by Suzanne Graham Storer and Mary De G. White, Hamden, Archon Books, 1980.)

In his book, not only does the author introduce us to the poetry of a beloved Chinese poet, but he opens doors to appreciating Chinese calligraphy through his own calligrahic interpretations. In the index, he then gives both figurative and literal interpretations in English which encourage the reader to conjure up their own images and wonder how they might create a poem in English which would begin to do justice to the images created by the Chinese characters. Here’s an example from the poem used as the title for this book. The English words were the literal translations provided by Professor Wang. Mary de G. White then took Professor Wang’s literal translation and created a poem which works in English:

Walking to Where the River Ends (行到水窮處)

行到水窮處,(walk, to, water, end, place)

xíng dào shuǐ qióng chǔ,

坐看雲起時(sit, watch, clouds, end, time)

zuò kàn yún qǐ shí。

偶然值林叟 (accidentally, meet, forest, old man)

ǒu rán zhí lín sǒu ,

談笑無還期 (chat, laugh, have not, return, time)

tán xiào wú huán qī

Walking to Where the River Ends by Wang Wei

“Walking to where the river ends

I sat and watched the clouds rise

By chance I met an old man in the forest

We talked and laughed

and forgot when it was time to go home.”

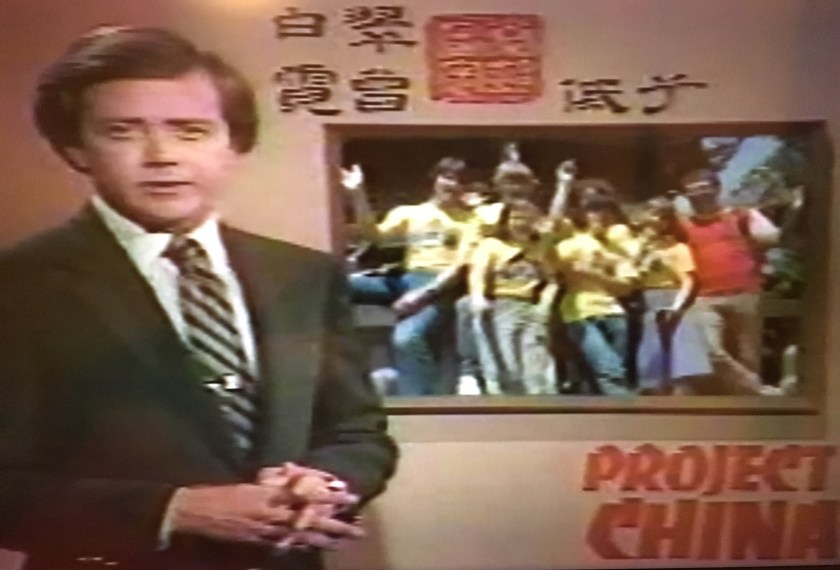

Chinese Odyssey 34

Trails wove through mountains

Running narrow and steep

hiding treasures which paintings —

and poetry — keep

reminding us how

little time has affected

the clouds and the cliffs

which the pools reflected.

Zhou Guanhuai [CC BY-SA 4.0 (

Zhou Guanhuai [CC BY-SA 4.0 (

According the The Oklahoma Historical Society, the Chinese were the first Asians to settle in Oklahoma. Soon after the 1889 Land Run, a Chinese entrepreneur set up the Tom Sing Laundry in Guthrie (near Oklahoma City). Other laundries and restaurants followed. The 1940 census showed only 110 Chinese living in Oklahoma. By 1980 that number had increased to 2,461. (

According the The Oklahoma Historical Society, the Chinese were the first Asians to settle in Oklahoma. Soon after the 1889 Land Run, a Chinese entrepreneur set up the Tom Sing Laundry in Guthrie (near Oklahoma City). Other laundries and restaurants followed. The 1940 census showed only 110 Chinese living in Oklahoma. By 1980 that number had increased to 2,461. (