By White House Photo Office (1969 – 1974) (White House Photo Office (1969 – 1974) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By White House Photo Office (1969 – 1974) (White House Photo Office (1969 – 1974) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In October, 1971, the United Nations recognized the Peoples Republic of China as the official representative government of China – and Taiwan was expelled.

Just a few months prior to that, the American ping pong team had been invited to China. This was the beginning of “ping-pong diplomacy,” which was soon followed up by Henry Kissinger taking a circuitous route through Pakistan to China to pave the way for President Richard Milhaus Nixon to travel to Beijing in 1972, where he met with Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou En Lai. From that trip, came the “Shanghai Communiqué,” where both China and the United States agreed that there is only one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. Although, the United States clearly asserted that it wanted a peaceful resolution to the “Taiwan Issue,” President Nixon also made it clear that he was not in favor of “Taiwan independence.”

Following their meeting, unofficial Liaison Offices were set up in both Beijing and Washington D.C. in 1973 while Taiwan continued to have it’s Chinese Embassy in Washington D.C. until it morphed into the Coordination Council for North American Affairs in 1979. Today, it is goes under the name, the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office in the United States.

In Viet Nam, the Paris Peace Accords, officially called the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam, was signed by representatives of the USA and Vietnam on January 27, 1973, but the war did not really end until the fall of Saigon in April of 1975.

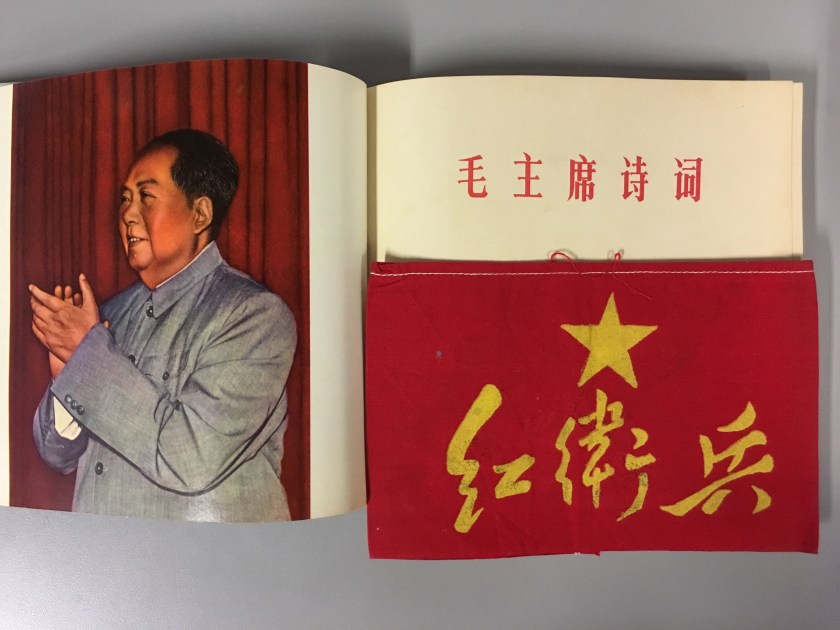

In China, the Cultural Revolution officially ended in 1976 when the “Gang of 4” (四人幫Sì Rén Bāng) – which included Mao Zedong’s wife, 江青 Jiāng Qīng aka Madame Mao – were all tried and sent to prison only months after Mao’s death. Shortly after Mao died, Deng Xiaoping (邓小平 Dèng Xiǎopíng), a different kind of revolutionary leader emerged who understood that China needed to change in ways very different from those of Mao and that meant not only serious reforms in China’s economic policies, but the breaking down of the “bamboo curtain” and an opening of China to the world.

It was Polish-American National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski who served under President Jimmy Carter, chief negotiator Leonard Woodcock, and Deng Xiaoping, the Paramount Leader of China who crafted the agreement that would formalize diplomatic relations between China and the USA in 1978. In this agreement, the USA reaffirmed the “one China policy” and declared that Taiwan was a part of China. The USA also insisted that it be allowed to “maintain cultural, commericial, and other unofficial relations with the people of Taiwan.” The official “denormalization” announcement came on January 1, 1979. The Armed Force Radio Taiwan (renamed ICRT in 1979), the English radio station in Taiwan, suggested that Americans living in Taiwan should probably stay close to home for the next couple of days. To those of us living in Taiwan then, it came as a shock. Nobody knew quite how to react, so life pretty much carried on with very few incidents.

Chinese Odyssey 24

Instead, “Made in China”

was on every thing

from toys and clothing,

to music and rings.

China opened its doors

and we were invited;

the flame which had smoldered

had been re-ignited.