Reading and writing Chinese is difficult. The US based Foreign Service Institute classifies Chinese as a Category 5 language (along with Arabic, Japanese, and Korean) for speakers of English. French and Spanish are classified as Category 1 because of the large number of cognates they share with English. There is very little that is intuitive about learning Chinese for a person growing up outside of a Chinese language environment. There is no phonetic alphabet which helps readers and writers of many languages to “sound out” words and spell them phonetically. Of course, Chinese parents and siblings read children’s books to children so kids learn to recognize characters before they learn to write them. And when they do start learning to write characters, close attention is paid to how they hold the writing instrument and how to write each stroke. Even though it is labor intensive work that requires a huge investment of time and effort, the 2018 CIA Factbook claims a literacy rate in Taiwan of 98.5%; in mainland China, 96.4%.

That said, few people educated outside of a Chinese education system have ever become truly literate in Chinese. The number of people who have studied and are studying Chinese outside of China has grown by leaps and bounds, yet the number of people who can pick up a Chinese newspaper, magazine, or book and easily read them is still relatively small, and of that number, those who can write and publish in Chinese is miniscule.

With all that in mind, here are some “organic” lessons I stumbled upon during my own journey.

Single character confusions

- Car license plates – During my travels in Guangdong, I grew curious when I saw the character 粵 Yuè at the beginning of every license plate. I was told that 粵 Yuè was an abbreviation for Guangdong. It came from the historical kingdom of Yue of which Guangdong was a part; The character 京 Jīng on license plates in Beijing made more sense since I knew that 京 Jīng meant capital and Beijing is the capital of China; 闽 Mǐn for the province of Fujian also confused me. I knew that Taiwanese was also called the Minnan dialect. The word Min comes from the Min river in northern Fujian and is an abbreviation for Fujian.

- Numbers – The numbers 1-10 are some of the easiest characters to learn in Chinese. Because they’re so easy, when writing a check and in other financial transactions, numbers are easy to alter. To address this, there is another way of writing numbers. A zero in Chinese is often written like this, “0”. The word for zero and the character used in finance, however, is 零 líng. The number one requires only a single stroke 一 yī. The number one used in finance, however looks like this, 壹y ī; two (二èr) becomes 贰 èr, five (五wǔ) becomes 伍, ten (十shí) becomes 拾, etc.

- Others – I used to get really confused when I went to the market and saw a sign saying 7折 (qī zhé). In the market place, Chinese often use Arabic numerals for convenience sake. It turns out that the character 折 (zhé) means “discount”. But 7 折 doesn’t mean 7% or 70% off. It means 30% off or 70% of the original cost.

Abbreviating names of institutions – In the same way Americans refer to Oklahoma University as OU and Brits refer to Manchester United as Man Utd, China has similar abbreviations.

- National Taiwan University (Táiwān Dàxué 台灣大學) →台大 Tái Dà

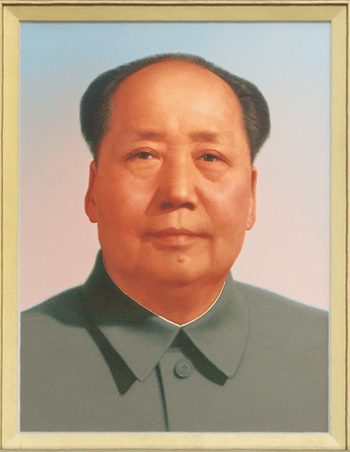

- Communist Party of China (Zhōngguó Gòngchǎndǎng 中國共產黨) → 中共 Zhōng Gòng

- One Belt One Road 一带一路 refers to the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century’s Oceanic Silk Road (丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路)。The 带 (belt) refers to multiple “Silk” roads and the 路 (road) refers to the oceanic trade route .

- Chinese-American 中美 Zhōng Měi, as in Chinese American friendship 中美友谊Zhōng Měi yǒuyì and Chinese American relations 中美关系 Zhōng Měi guānxì

Up down, right left, and left right – In the old days Chinese sentences and phrases were always written from top to bottom and from right to left. Books in Chinese seemed to be read “from back to front”. It wasn’t until the mid-20thcentury that writing horizontally started appearing on the scene in China. A big part of the reason for doing this had to do with making the learning of Chinese easier. If Pinyin is included in the text, it is much easier to input words horizontally than vertically. Today, it is still common to see Chinese phrases and sentences written both vertically and horizontally. What can be confusing to the newcomer is when a horizontal sentence or phrase is written from right to left. Occasionally there are signs where both right to left and left to right are used. Then, one has to rely on context.

Fonts and styles– There have always been different styles of writing in Chinese. The style of Chinese writing beginners start with could be compared to printing letters in English. Although we don’t think of it now, most of us learned how to hold a pencil and the correct order for writing our letters. After printing, came cursive, and after cursive came calligraphy. There are probably at least as many fonts and styles of written Chinese as there are of written English. To illustrate this, I used to write “The United States of America” on the white board as fast as I could and purposely tried to make it illegible. Although I made it so hurried that not one letter could be distinguished, invariably a student would see “The United States of America”. In some of the most beautiful calligraphy in Chinese, individual strokes are impossible to pick out, but due to the rules of stroke order, it is obvious what the character is.

Cantonese expressions– When I first arrived in Hong Kong, I thought picking up Cantonese would be a breeze. Not so. I have all sorts of excuses. More tones. Too colloquial. No standard form of Romanization. Characters like 冇 (meaning “not have”) don’t even exist in Mandarin. Nor do expressions like the word for store, si6 do1 (士多) and taxi – dīk-síh (的士) which are transliterations from English. Still, I think my basic flaw was laziness. So many people spoke English when I arrived in Hong Kong that I wasn’t forced to learn Cantonese. Now, more people in Hong Kong speak Mandarin than English, so that has become my goto language. Still, I don’t see Cantonese on its way out. It is an incredibly rich dialect of Chinese with a long history. Many scholars say that Tang Dynasty poetry read in Cantonese is much closer to what the poems sounded like when they were written. Then, there’s Canto-pop!

Chinese Odyssey 14

Street signs were my textbooks,

bus stops, bills, and menus;

quizzes and tests

were all about venues.

Thrown into the water

I’d learned how to swim

and the jar with the map

was a memory dim.