One of my favorite Stephen Spielberg movies is “Empire of the Sun.” I love seeing the young Christian Bale playing the role of J. G. Ballard, the author of the book by the same name. I also marvel at the access Speilberg got to Shanghai as it was transitioning from the ravages of the Cultural Revolution to the boom of the 1990s. The opening shots of the film remind me of a quote from J.G. Ballard’s novel:

“Every night in Shanghai those Chinese too poor to pay for the burial of their relatives would launch the bodies from the funeral piers at Nantao, decking the coffins with paper flowers. Carried away on the tide, they came back on the next, returning to the waterfront of Shanghai with all the other debris abandoned by the city. Meadows of paper flowers drifted on running tide and clumped in miniature floating gardens around the old men and women, the young mothers and small children, whose swollen bodies seemed to have been fed during the night by the patient Yangtze.”

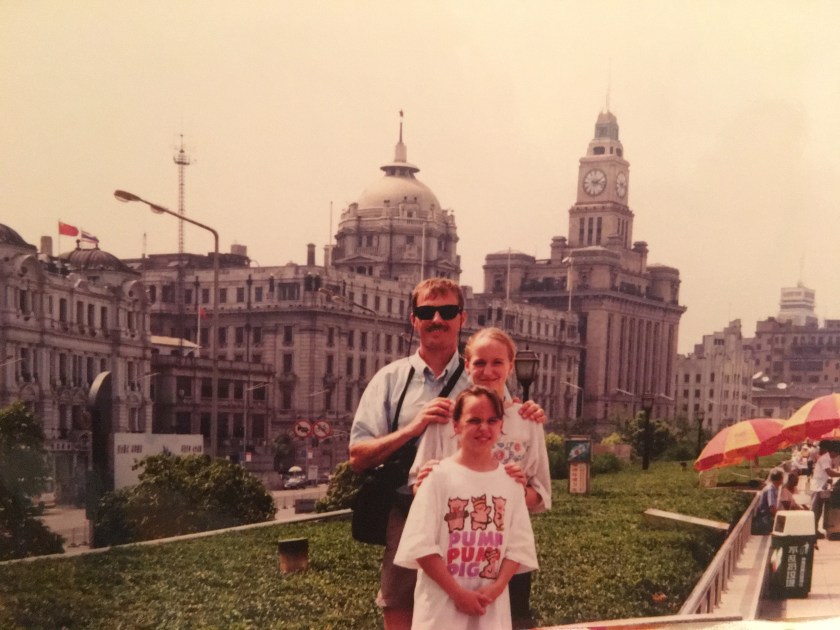

With its current population of 24 million plus (nearly 3 times that of New York City), Shanghai is the most populous city in the world (within a single administrative region.) Although Shanghai displays some of the world’s most modern architectural structures, it has also decided – at least for the moment – to preserve one of the richest collections of art deco architecture of any city in the world. The Bund (外滩 Wàitān) remains the image which comes to the minds of many Westerners when they hear the name, Shanghai. The word, “bund” is a hybrid Persian, Hindi, English, and German word with the original meaning “embankment”. The traditional Bund is a mile-long stretch along the river in Puxi. Pu is short for Huángpǔ (黄浦江), the river which divides Shanghai into Pǔxī 浦西 (west of the Huangpu) and 浦东 Pǔdōng (east of the Huangpu). Along the two sides of the Huangpu now stands the 2017, 128 story, energy efficient, typhoon resistant Shanghai Tower上海中心大厦, the 2008, 101 story Shanghai World Financial Center上海环球金融中心, and the hybrid modern/art deco 88 story Jin Mao Tower金茂大厦 (1999), alongside the 10 story Fairmont Peace Hotel上海费尔蒙和平酒店(1926), the 17 story Bank of China Building 中国银行大厦 (1937), and the iconic Cathay Theater 国泰电影院 (1932). Shanghai is definitely worth visiting for its architecture alone.

The city of Shanghai is one of four Municipalities (直辖市 Zhíxiáshì) in China. The other three are Beijing, Tianjin, and Chongqing. A municipality in China operates in a similar way to the District of Columbia in the USA. Municipalities are not considered to be part of any province. Municipalities are under the direct administration of the Chinese central government.

In the 1920s, Shanghai was known as the “Paris of the Orient”, and was China’s most international city. There was opulence sitting next door to abject poverty. Whitey Smith played jazz in the Astor House, the Paramount, and the Fairmont. The Green Gang lead by Big Eared Du (杜月生 Dù Yuèshēng) controlled the lucrative opium and heroin trade. The latest Hollywood films showed at the Cathay Theater, and flappers wore the same outfits and hairstyles as their counterparts did in New York, London, and Tokyo.

Shanghai was also a city of politics. The first congress of the Communist Party was held in Shanghai in July 1921. It’s formal name, Zhōngguó Gòngchǎn Dǎng 中國共産黨 was also established at that time. Just two years prior to that, the May 4th movement (五四运动 Wǔsì Yùndòng) had erupted in Beijing partially due to the granting of European concessions to the Japanese in Shanghai and partly to protest against the 21 demands made by the Japanese directed at China. In 1927, a youthful Chiang Kai-Shek, recognizing the imminent threat of the Communists to his Guomintang (KMT) Party, conducted what became known as the Shanghai Massacre, when he sent in his troops and conscripts from the infamous Green Gang to wipe out the Communist scourge from Shanghai. By 1934, the Communists were pretty much gone from Shanghai, with most following Mao on the Long March.

Another classic 1920’s mansion, Shanghai’s Jinjiang Hotel (锦江大酒店), formerly the Cathay Mansion, was the site of the historic 1972 meeting between US President Richard Nixon, and Premier Zhou Enlai where the Joint Communique of the USA and the PRC aka the Shanghai Communique, reopened the relationship between the US and China.

Like its “sister city”, Hong Kong, 1200 km to the south, Shanghai has always prided itself as an international city. And there is definitely a friendly rivalry which exists between these two behemoths. Although Shanghai’s population is three times that of Hong Kong, Hong Kong’s population density is nearly twice that of Shanghai. At age 32, Shanghai’s median age is 10 years younger than Hong Kong. Rent in HK is roughly double that of rent in Shanghai. Transportation is twice as expensive in Hong Kong, but ease of transportation has Hong Kong far exceeding Shanghai. That is one of the main reasons that Hong Kong is easier for families than Shanghai. Getting a Hong Kong drivers license is fairly simple and many ex-pats have cars. More would if parking was less expensive and more accessible. The internet is reasonably fast in Hong Kong and there are no firewalls preventing communication of controversial topics. Both private and public medical care are easily accessed in Hong Kong and there are always competent English speakers for those who don’t speak Chinese. Restaurant food’s cheaper in Shanghai, but both places sport some amazing eateries. I think if I was young and single, I might choose Shanghai over Hong Kong just because of its potential. Being neither young nor single, however, Hong Kong’s definitely the place for me.

Chinese Odyssey 37

Our leisurely train went

northeast to Shanghai.

The Bund was amazing!

We all wondered why,

in the middle of China

the majestic Huangpu

mirrored art deco skylines —

split Shanghai in two.

CHINA: EMPEROR AND BOATS. – Yang Ti, Sui emperor of China (604-618), and his fleet of sailing craft, including a dragon boat being pulled along the Grand Canal. Painted silk scroll, 17th century.. Fine Art. Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2016.

CHINA: EMPEROR AND BOATS. – Yang Ti, Sui emperor of China (604-618), and his fleet of sailing craft, including a dragon boat being pulled along the Grand Canal. Painted silk scroll, 17th century.. Fine Art. Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2016. Qin Hui and Lady Wang – Morio [CC BY-SA 4.0 (

Qin Hui and Lady Wang – Morio [CC BY-SA 4.0 (

Zhou Guanhuai [CC BY-SA 4.0 (

Zhou Guanhuai [CC BY-SA 4.0 (