Chinese Odyssey 63

We opened a door

in the sky and stepped through.

Wulumuqi to Xi ‘An

on carpets, we flew.

In the History Museum

we wandered through time,

found ancient inventions

and poems without rhymes.

The Han Dynasty lasted more than 400 years – from 206 BCE to 220 CE. In many ways, it defined much of what China was to become. To this day, over 90% of the people in China consider themselves to be Hàn Rén 漢人 (lit. people of the Han) and the Chinese language in its totality is referred to as Hàn Yŭ 漢語 (the language of the Han). A hǎohàn 好汉 in China is “a good guy.” The Han Dynasty produced some of the coolest inventions ever: Chinese paper was invented then, as was moveable type, instruments for measuring seismic activity, wheel barrows, suspension bridges and many other amazing innovations were said to have been invented during this longest of the Chinese dynasties.

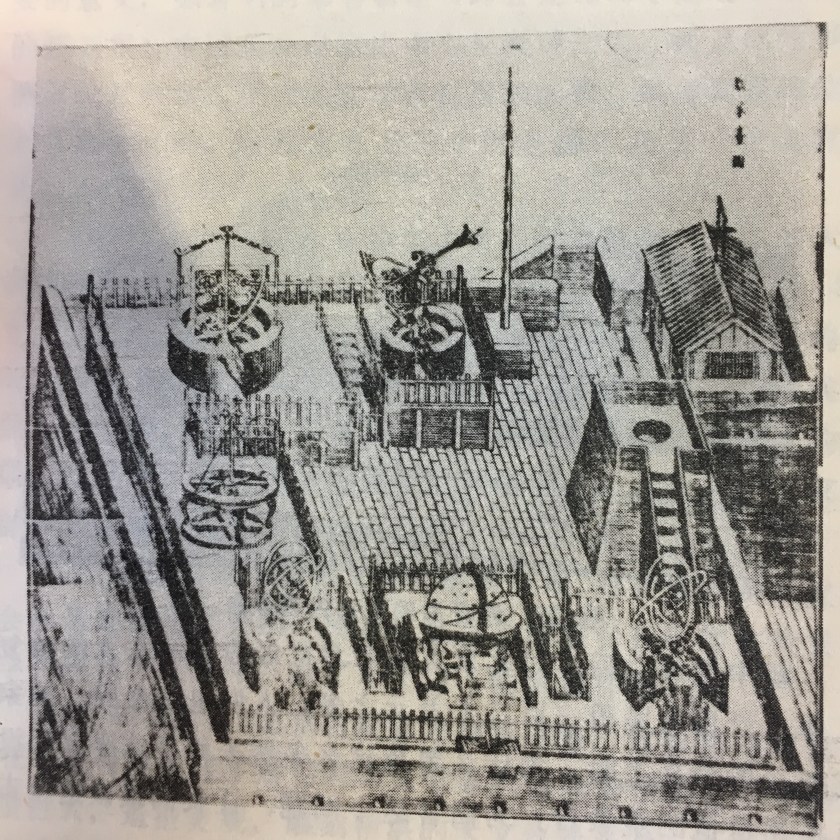

One of the first exhibits to catch my eye at the Shaanxi History Museum was a tea pot with no lid. When the teapot was turned over there was a clay funnel built into the bottom of the teapot and scalding water would have been poured into the clay funnel. Turn the teapot right side up and the tea stayed in the pot. I’m still not sure how they put the tea leaves into the pot, though or how the inside of the pot was cleaned. Then there was the goose shaped smokeless bronze lamp. The smoke from the flame of the burning lamp went up through the long neck of the goose and back into the body of the lamp which contained water and there the smoke would die. One sided mirrors and coins with squares cut out of them. Water wells and grain grinders, axes and adzes, and even a Han loom that looked modern all were exhibited at the Shaanxi History Museum. From the Tang Dynasty there were wine pots made out of silver and drinking cups in the shape of horns mad out of agates. One of the most famous paintings there from the Tang Dynasty had five men mounted on horses playing polo English style.

The place we now call Xi’an had a different name up to the beginning of the Ming Dynasty (14th Century). Chang’an was actually a few km northwest of the modern city of Xi’an. Chang’an loosely translates to Eternal Peace. It’s founders tried to insure that by positioning Chang’an near both the Huang He and the Wei rivers in an area surrounded on all sides by hills. Artifacts found near the site of Chang’an pre-date the Shang Dynasty and by the end of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (771-256 BCE) Chang’an was China’s capital. At that time, Chang’an was one of the largest cities in the world having close to one million people. Chang’an was also China’s capital during the Han, the Sui (581-618 CE) and the Tang (618-907 CE) dynasties.

Chang’an was the eastern portal to the Silk Road. It was in 128 BCE during the Western Han Dynasty when Zhang Qian (張騫 Zhāng Qiān) , a young imperial officer, was sent by Emperor Han Wu Di (漢武帝 Hàn Wǔ dì) from Chang’an to explore the Western region to try to establish a military alliance with the Kingdom of Yuezhi in modern day Tajikistan. To do that, he needed to go through Inner Mongolia which was controlled by the Xiongnu (匈奴Xiōngnú). Zhang Qian was captured by the Xiongnu in the Hexi Corridor and held captive for more than 10 years. While a prisoner Zhang Qian married a Xiongnu woman who bore him a son. When the Xiongnu leader died, Zhang Qian and his good friend and guide, Ganfu (甘父 Gān fù) escaped with Zhang Qian’s wife and son, but instead of returning to Chang’an, they continued north to Khöshöö Tsaidam in modern day Mongolia and then followed the northern edge of the Tarim Basin , around the Kunlun mountains, and even stopped at Kashgar. They then continued west to Ferghana (modern day eastern Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan), and south to Bactria. While in Bactria (present day Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan), Zhang Qian learned about Alexander the Great and this was the first recorded meeting between these great civilizations. On their journey home, Zhang Qian’s entourage traveled east below the Tarim Basin and crossed the Gobi Desert before eventually reaching Chang’an.

Zhang Qian was much more successful in his second journey to the west when he was accompanied by 300 men to present day Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan. Although Zhang was unable to visit India and the Macedonian and Parthian Empires, he did learn valuable information about those regions. On his journey back, Zhang Qian was able to bring back alfalfa and grapes which grew easily in the western regions of China. He also brought back stories of horses from the Fergana valley (located between Kyrgystan and Tajikistan) which Han Wu Di renamed “Heavenly horses” (大宛馬 dàyuānmǎ aka 宛馬 yuānmǎ). Han Wu Di sent 20,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry west to the Fergana valley to obtain these horses, but lost half of his soldiers along the way and they lost the first “War of the Heavenly Horses.” The Emperor was not happy so he sent another bigger force of 60,000 mostly prison recruits and 30,000 horses and they had no problem making there way to Dayuan (Fergana) and after a 40 day siege, the Han forces achieved victory. In the end, the Han General left Dayuan with 3,000 horses of which around 1,000 Heavenly Horses, the Lamborghinis and the Aston Martins of China 2000 years ago, finally arrived in Chang’An in 101 BCE.

“The Arrival of the Heavenly Mare”

天馬徠兮 從西極

經萬里兮 歸有徳

承靈威兮 降外國

渉流沙兮 四夷服

The heavenly horses have arrived

from the Western frontier

Having travelled 10,000 li,

they arrive with great virtue

With loyal spirit,

they defeat foreign nations

And crossing the deserts

all barbarians succumb in their wake!

–The Shiji, Chapter 24 (“The Treatise on Music”) Shiji (史記) vol. 24, “Yueshu (楽書)” number 2.

Hiroki Ogawa [CC BY (

Hiroki Ogawa [CC BY ( Siim Sepp [CC BY-SA 3.0 (

Siim Sepp [CC BY-SA 3.0 (

wikimedia.org/wiki/File:One-belt-one-road.svg

wikimedia.org/wiki/File:One-belt-one-road.svg