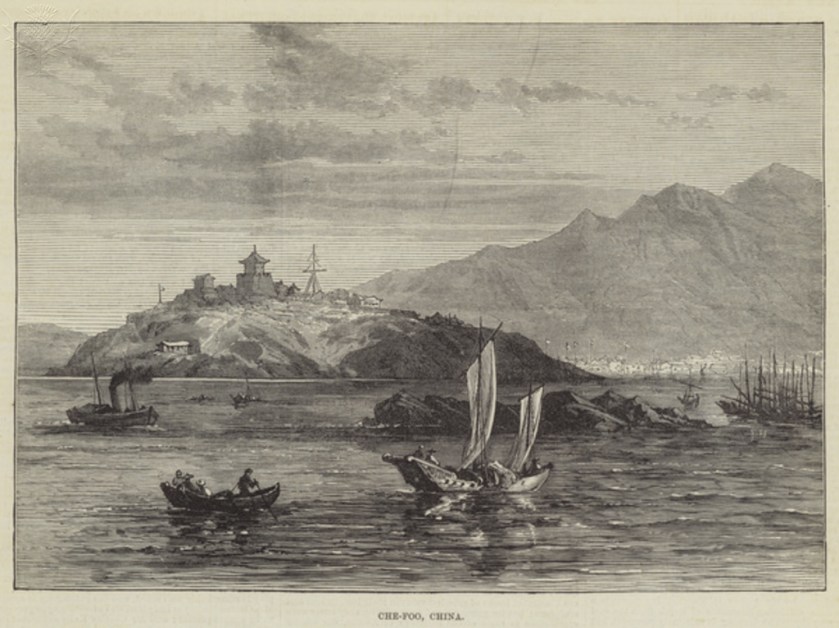

Che-Foo, China (engraving). Illustration. Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 26 Mar 2018. quest.eb.com/search/108_2472893/1/108_2472893/cite. Accessed 16 Mar 2019.

Che-Foo, China (engraving). Illustration. Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 26 Mar 2018. quest.eb.com/search/108_2472893/1/108_2472893/cite. Accessed 16 Mar 2019.

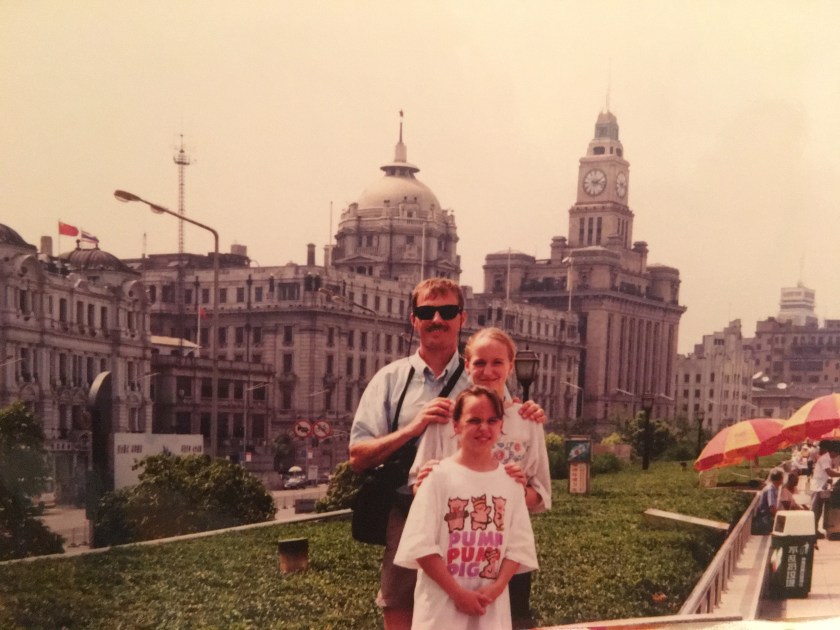

In 1997, the plan was to travel by train from Taishan to Yantai. Yantai (烟台市 Yāntái shì) is located on the southern shore of the Bohai Sea which turns into Korea Bay and then becomes the Yellow Sea and then the East China Sea and finally the Pacific Ocean. It is nearly due south of Dalian (formerly known by non-Chinese speakers as “Port Arthur”), and it looked to be a straight shot by boat to Tianjin. Twice I tried and twice my plan was foiled. But I’d still like to ride that boat.

Chefoo 芝罘 Zhīfú was the name most Westerners used when they referred to the city we now know as Yantai. Although it is a city of nearly 7 million people, my guess is that many people reading this have never heard of it. There was a Christian school that opened there in 1881 called the Protestant Collegiate School or Chefoo China Inland Mission School 芝罘学校 Zhīfú Xuéxiào, and it served as a Christian boarding school for the China Inland Mission. I find the accounts of Christians living in China fascinating. More came to teach than to learn. The ways they lived and dressed and considered their missions were multifold and multi-layered. Many provided the first solid connections between China and the West. Some men and women would dedicate their entire lives to the service of the church in China. I found this account of the life of missionary children at the Chefoo School by Larry Clinton Thompson, an interesting window into how the children of these missionaries lived their lives: https://www.academia.edu/8994079/Missionary_Children_in_China_The_Chefoo_School_and_a_Japanese_Prison

In 1941, the children and staff who had not managed to leave before the Japanese invaders arrived were first interned in the Temple Hill Internment Camp in Chefoo before being transferred to the larger Weihsien Internment Camp 潍县集中营 Wéixiàn Jízhōngyíng, a Japanese operated “Civilian Assembly Center” about 260 km southwest of Chefoo. Among the residents of the camp was Eric Liddell, the famous Scottish gold medal runner turned missionary who was featured in the 1982 Oscar best picture film, “Chariots of Fire.” When he was finally taken prisoner by the Japanese, he was sent to Weihsien where he continued his ministry, setting up sports events, teaching science to children, and running a Sunday school every week. While there, he was diagnosed with a brain tumor but was inspirational to the end. The title track from “Chariots of Fire” is often used in sporting events today and is still one of the most recognizable instrumental movie themes ever written.

A fun story connecting Yantai to the West involved an American sailor by the name of Jimmy James. Most people don’t know that Jimmy’s actual last name was Skalicky. After dropping out of college in Minnesota in 1902, Jimmy joined the army and ended up in Tianjin (then known by Westerners as Tientsin) where he was discharged from the 15th Infantry in 1922. At that town, there were naval ships that would dock at Yantai, and Jimmy had the bright idea of opening up a hamburger stand there. It was such a big hit, people begged him to do something similar in Shanghai, so Jimmy decided to give it a go. In 1924, he opened up a diner on Broadway Road (now Da Ming Lu) in Shanghai, called The Broadway Lunch. In 1927, he changed the name to Jimmy’s Kitchen, and the rest is history. And for those who don’t know that history . . . the restaurant is an icon in Hong Kong from the Colonial era. You can still get the same Steak Diane and Baked Alaska that were favorites of John Wayne and Cary Grant. Still dishing up great grub on Wyndham Street in Central and at the Jinjiang Hotel in Shanghai.

Chinese Odyssey 42

On the map it appeared

to be one easy sail

from Yantai to Tianjin;

there was no way to fail.

No boats in the Bohai,

so an overnight bus

where the seats turned to beds

was a hotel for us.

Kent Wang from Richmond, Vancouver (

Kent Wang from Richmond, Vancouver (

CHINA: EMPEROR AND BOATS. – Yang Ti, Sui emperor of China (604-618), and his fleet of sailing craft, including a dragon boat being pulled along the Grand Canal. Painted silk scroll, 17th century.. Fine Art. Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2016.

CHINA: EMPEROR AND BOATS. – Yang Ti, Sui emperor of China (604-618), and his fleet of sailing craft, including a dragon boat being pulled along the Grand Canal. Painted silk scroll, 17th century.. Fine Art. Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2016. Qin Hui and Lady Wang – Morio [CC BY-SA 4.0 (

Qin Hui and Lady Wang – Morio [CC BY-SA 4.0 (